With hundreds dead on both sides, the war between Armenian and Azeri forces in Karabakh — in Armenian, Artsakh — a mountainous enclave in the Southern Caucasus, is now anything but ‘frozen’, as it has long been described. A tenuous ceasefire had held since 1994, when the population of this historically Armenian region secured its de facto independence, in close cooperation with the Republic of Armenia. Peace has mostly prevailed since then, except for a four-day war in 2016 and a major flare-up last July.

The immediate cause of the fighting that broke out on 27 September is Azerbaijan’s attempt to reclaim territory that was within its borders during the Soviet period. After the Caucasian Bureau of the Bolshevik Party initially recognised Karabakh’s right to autonomy and promising it to Armenia following the republic’s sovietisation in 1920, Joseph Stalin, then commissar of nationalities of the Soviet Union, intervened, and the Soviets gave Karabakh to Azerbaijan in 1921. Armenians argue that this decision flies in the face of its history of continuous autonomy under Armenian princes since at least the eighth century and, more importantly, its population being more than 90% Armenian. In 1923, the Soviet government proclaimed the enclave an autonomous region within the Socialist Soviet Republic of Azerbaijan.

A complex set of factors contributed to this decision, including concessions to the Soviet rulers of Azerbaijan and, more importantly, Soviet leader Vladimir I. Lenin’s flirtation with Turkey’s Mustafa Kemal. The Kremlin was pursuing internationalist policies in the early 1920s to spread the Russian Revolution throughout the world, and the emerging Turkish Republic — where Kemal was apt to play off foreign powers against each other for his own benefit — was an alluring prize.

These recent clashes, however, amount to full-fledged war, with a dangerous, new actor: Turkey, which had previously remained on the sidelines. The significance of active Turkish military intervention, with military officers directing attacks, cannot be overstated. Turkey’s active involvement in the conflict signals an escalation of existential importance for Armenia. As political scientist Anna Ohanyan, professor of political science and international relations at Stonehill College, says: ‘The Armenian genocide is not a footnote to the Armenian-Azeri conflict; it is at its core.’

An unrecognized genocide

The first reason for this is ‘Turkey’s singular unrepentance for the twentieth-century genocide’, which ‘remains today the most elemental obstacle to peace,’ as Ohanyan wrote in an analysis of the conflict. ‘It is little appreciated that many of modern Armenia’s statespersons, including presidents and foreign ministers, and more than half of Armenia’s adult population, are children or grandchildren of survivors of that genocide.

As recently as May 2020, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan referred to Armenians as ‘kılıç artığı’, a pejorative in Turkish that means ‘remnant of the sword,’ in reference to genocide survivors. ‘As Genocide Watch cautioned, it reflected an evolution of mindset on the Armenian genocide, from one of crude denial to an explicit ‘pride of the perpetrators,’ Ohanyan writes. ‘It is the rhetorical equivalent of a German leader taunting Israelis as remnants of Nazi extermination camps. The leap to viewing the entirety of modern Armenia as a “remnant of the sword” is not great.’

Indeed, in his successive calls for mobilization after the war broke out, Armenian prime minister Nikol Pashinyan said that the country was faced with a ‘life or death’ moment in its history and called on every Armenian to defend the nation against annihilation attempts by the combined Turkish-Azeri forces. ‘The Turkish state, which continues to deny the past, is once again venturing down a genocidal path,’ Pashinyan has said. Historian Bedross Der Matossian, of University of Nebraska Lincoln, agrees that the unresolved trauma of the genocide compounds the conflict.

‘The anti-Armenian discourse fuelled by both governments in Turkey and Azerbaijan and their military actions against the vulnerable Republic of Armenia are manifestations of genocidal tendencies of both authoritarian regimes,’ Der Matossian says. ‘Turkey’s role in this war is specially alarming due to its historical record of mass violence against minority groups within and outside its borders.’

Armenians truly believe that the coordinated and premediated military offensive by Azerbaijan and Turkey are part of ‘finishing the project that began a century ago’. Consequently, ‘the Armenians are fighting an existential war: the stance of the international community is appalling, the majority of which demonstrate intoxicated neutrality.’ As Armenia is relatively poor, lacking oil to fund a modern army, it depends on Russia for security.

Azerbaijan’s minimalist and maximalist goals

Yet Der Matossian believes that Azerbaijan is pursuing more limited goals. ‘At first glance it seems that Aliyev’s minimalist goal is to reclaim back the additional territories around Artsakh (Nagorno-Karabagh) which are under Armenian control,’ he says. ‘His maximalist aim is to occupy the Republic of Artsakh.’ He doubts the latter will happen. ‘Aliyev wants to come out from this war at least “liberating” some territories from the additional sections in order to strengthen his shaky authoritarian regime.’

The collapse of oil prices would further compromise Aliyev’s authoritarian regime’s already unstable hold over his increasingly restless population, in a country with massively unequal wealth distribution. Decreasing oil income would result in higher taxation, predicts Ohanyan. ‘Taxation without representation’ would further undermine his autocracy.

Armenian American historian Gerard Libaridian is wary of predicting a genocide in the making. He does believe, however, that ‘the maximum that Turkey and Azerbaijan wanted to achieve was to ethnically cleanse Karabakh of Armenians.’ That scenario, he says, ‘does not exclude inflicting casualties among the civilian population: in fact, striking at that population and instilling fear in them is part of the strategy.’ Libaridian served as senior adviser to Levon Ter Petrossian, the first president of Armenia after the country regained its independence from the Soviet Union in 1991 and he was closely involved in the Karabakh negotiations.

Neo-Ottomanism and pan-Turkism

The second reason for Armenian concern about Turkey’s intervention is pan-Turkism, an integral part of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s neo-Ottomanist ambitions. The unification of what is now Turkey’s Asia Minor mainland with Azerbaijan was first pursued in the waning days of the Ottoman Empire.

Indeed, Enver Pasha, one of the ideologues and executors of the Armenian genocide, led the effort in 1918 to create what became Azerbaijan, as part of the Ottomans’ pan-Turkist policies. That the Azeri nation-making initiative was implemented by the Special Organization (Teşkîlât-ı Mahsûsa), the blandly named Ottoman government branch that put into practice the 1915 genocide, and by Nuri Pasha, Enver’s brother, entwines the birth of Azerbaijan with the genocide. Furthermore, Nuri Pasha led the Ottoman war effort against the Italians in Libya, where Turkey is now active again.

‘In 1993, Turkey unilaterally closed the border with Armenia by becoming a party to the conflict and siding with Azerbaijan,’ says Irina Ghaplanyan, deputy minister of Environment of Armenia. ‘Turkey’s intervention in the conflict hence dates back to 1993.’

Read also Philippe Descamps, “Flare-up in Nagorno-Karabakh”, Le Monde diplomatique, December 2012.

Turkey’s current intervention, however, signals an unprecedent escalation, Ghaplanyan warns, with its ‘very open, emboldened and unchecked position of supporting Azerbaijan in its aggression against Artsakh and Armenia by means of supplying Azerbaijan with weapons, high ranking military command, areal and ground combat support and hired mercenaries.’ Ghaplanyan says this is ‘a proxy war for Turkey, one of many that it has started over the past few years with the goal to reinstate its once dominant status in the region: Ankara employs a big arsenal of tools ranging from providing open military and political support to other dictatorships or separatist groups, to attempting to redraw borders.’

With an isolationist White House under President Donald Trump, the United States — absorbed in its political crises and the upcoming presidential elections — having renounced its role as policeman of the world, Erdoğan may have sensed this is a historical opportunity to put his neo-Ottomanist expansionism to test, with his country now actively involved in at least nine wars or conflicts from Libya to the Caucasus. Der Matossian sees an imperial push in Erdoğan’s intervention in the war. ‘Turkey’s goal is to extend its influence over the Caucasus as part of his megalomaniac ambition of creating an Empire or even the illusion of it.’

Unequal rivals

Armenia finds itself again at the crossroads where the interests of three empires clash. For Russia, Turkey and Iran are still empires in all but name in terms of geography, demography and ambitions.

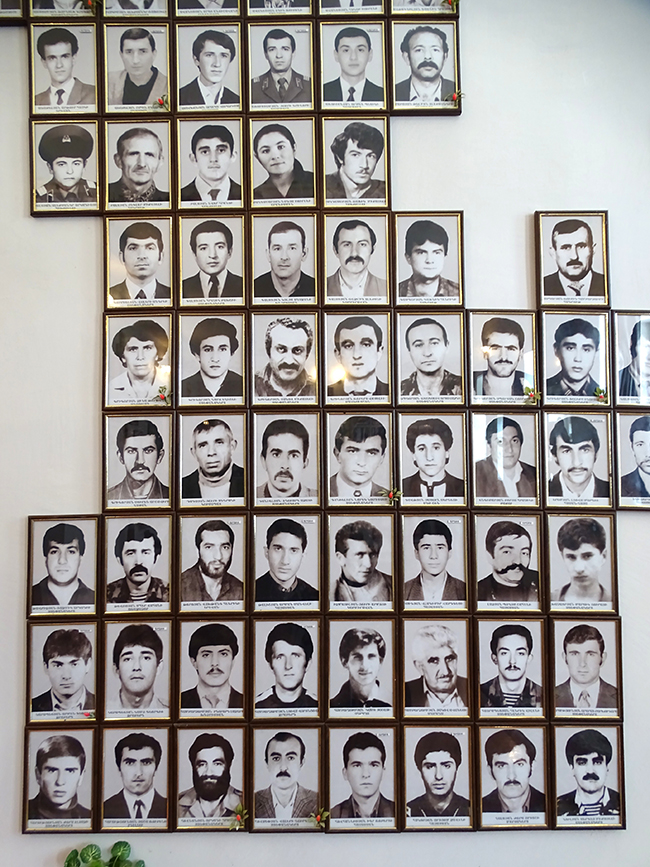

‘Unequal fights have been a common feature of Armenian history, becoming a symbolic representation of heroism against all odds,’ says Vartan Matiossian, independent historian and literary scholar in New York. ‘From the emblematic battle of Avarayr in the fifth century between Armenians and numerically vastly superior Persians in defence of Christian faith to the crucial battle of Sardarabad in 1918 between a haphazardly gathered Armenian forces and a well-organized Ottoman Turkish army, such episodes have peppered the past and brought their perception into the present. The first Karabakh war of 1992-1994 was also seen in that light, and it is not by chance that the current Azeri attack has been regarded as a repeat of a kind of historical constant.’

Stephan Astourian, history professor at Berkeley University, points out that the Azeri war effort is now being led by Turkish army, whereas Turkish foreign minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu seems to dictate its wartime diplomacy, to judge from his prominent role in the fortnight since the Turkish-Azeri attack against Karabakh began. Astourian warns about dangerously naïve peace initiatives, such as the one advanced in 1992 by Paul Goble, of the U.S. State Department, who proposed land swaps that involved incorporating Zangezur into Azerbaijan while Armenia would get ‘part of the Nagorno-Karabakh’ (as the territory was known in the Soviet Union). Deprived of a land bridge to Iran, Armenia would be completely surrounded by two enemy parties — Turkey and Azerbaijan, which call themselves ‘one nation, two states’— and Georgia, nominally neutral but with commercial and military agreements that have made it an unreliable, at times hostile neighbour for Armenia.

For Turkey, ‘a land bridge with the main part of Azerbaijan is also a strategic goal,’ Astourian says. The next logical step would be territorial linkage with the rest of Azerbaijan and the resulting access to the Caspian Sea. ‘I don’t view the so-called ‘Goble Plan’ (1992), discussed until the late 1990s, as stemming from naive peace-restoring diplomacy,’ he says. Paul Goble, who is known for his anti-Russian views, recently joined the staff of Azerbaijan’s Diplomatic Academy.

‘The main prize in the medium to long term is the land bridge and, thus, Zangezur,’ Astourian says. ‘On the other hand, if [Armenia] loses this war, massive ethnic cleansing is to be expected.’

The occupation by the Artsakh army of Azeri districts around Karabakh in 1993, which was condemned by the UN, adds a further layer of complexity to an already intractable problem. This resulted in the destruction of villages and displacement of thousands of Azeris from those districts.

A new Great Game?

These views notwithstanding, Gagik Sarucanian, Armenia’s consul in Venice, suspects a larger game. ‘Azerbaijan has more focused goals: Aliyev needs to bring some sort of victory home for his domestic policy goals and shore up his regime,’ Sarucanian says. ‘But Turkey is a much bigger geopolitical actor; with the second-largest armed forces in NATO, it is playing a bigger game.’ He rules out the feasibility of a second genocide: ‘Armenia is now a sovereign state with a strong army,’ not a Christian minority at the mercy of Ottoman rulers.

Yet he suspects Turkey’s entrance in the war and its obvious attempt to gain a foothold in the Caucasus may have to do with plans against Iran. (One could argue that it may have to do with Russia, too, which exerts power in the region.) Sarucanian points to the large Azeri minority in northern Iran, which in case of further turmoil in the region could push for reunification with the Republic of Azerbaijan. Not only would that displease Iran’s rulers: it would also create propitious conditions for a potential attack against Iran by a coalition of hostile powers, including Turkey, from the territory of the Republic of Azerbaijan.

Read also Vicken Cheterian, “Armenian ghosts”, Le Monde diplomatique, April 2015.

Ghaplanyan says that Prime Minister Pashinyan has stated that the solution to the conflict has to be acceptable to all the parties concerned: Armenians of Artsakh, Armenians of the Republic of Armenia and the people of Azerbaijan. ‘Armenia has been very clear that the solution to the conflict has to occur only through negotiations, whereas Azerbaijan had for years been communicating the message that the conflict if not resolved in the framework of Azerbaijan’s territorial integrity, will be resolved through other means,’ she says.

Because of the memories of genocide that Turkey’s intervention awoke, this war has galvanized Armenians not only in Artsakh and Armenia, but also in the diaspora, in a manner unmatched by any other event in modern Armenian history. That explains the thousands of volunteers who flocked to the battlefront from communities all over the world, including Russia, Lebanon, Europe, the US and South America. ‘Whereas in other countries people flee when wars break out, Armenians are returning to the homeland to defend it,’ says Alex Soghomonian, of the Armenian monastery of St. Lazarus in Venice.

The fact of holding the battlefront before a combined Turkish-Azeri force that also includes battle-hardened mercenaries brought in from northern Syria has only added to the epic dimension of the war in the imagination of Armenians.